A century in the past, a century in the future: that’s the purview Ruth Mandl and Bobby Johnston, married architects who run CO Adaptive Architecture, had when renovating their three-story townhouse in the Bedford-Stuyvesant neighborhood of Brooklyn. “We wanted to celebrate and respect the building’s past,” says Mandl of the 1889 brownstone, “but update and fortify it for another hundred-plus years of use.”

The key to their centuries-spanning project was passive house design, which refers to a set of design principles for creating highly insulated, super-efficient and inherently comfortable houses primarily through the creation of an airtight envelope. “We kept or reinstated all the features we loved, including the intricate facade, the room proportions and the beautiful woodwork and plaster details, but upgraded the systems to modern standards,” explains Mandl. Then they capped the gas line off at the street and electrified everything. The result is a modern, airy and warm two-family building—there’s a rental unit on the garden level—that produces more electricity than it consumes. Here’s how they did it.

The benefits of passive house design

While this was CO Adaptive’s first passive house project, it wasn’t Mandl’s. The native Austrian worked as an architectural intern on the retrofit of a 1950s building in Vienna, originally constructed by her grandfather. “Then it was renovated to the passive house standard by my father,” she says. Getting to experience a passive house first-hand taught her a lot about its benefits, which she and Johnston now get to enjoy with their young daughter in their Brooklyn home. “The temperature is even and comfortable—there are no drafts, or hot or cold spots,” says Mandl. “It’s quiet, and the air is always fresh.”

When it came time to renovate their own house in Brooklyn, Mandl and Johnston chose a passive house approach for its durability. “You’re investing in the passive elements of a house—the envelope, good windows, insulation—and those are things that will last decades,” says Mandl, adding that active systems, like heating and cooling strategies, become outdated much more rapidly. “So those are kept to a minimum.”

What makes an existing building a good candidate for a passive house retrofit? Will any structure do?

“Most buildings lend themselves to passive house retrofits. Attached townhouses are great because you only need to insulate the front, rear, roof and lowest story. Essentially, the less surface area—so the simpler the shape—the easier it is to insulate and air seal.”

— Ruth Mandl, principal at CO Adaptive Architecture

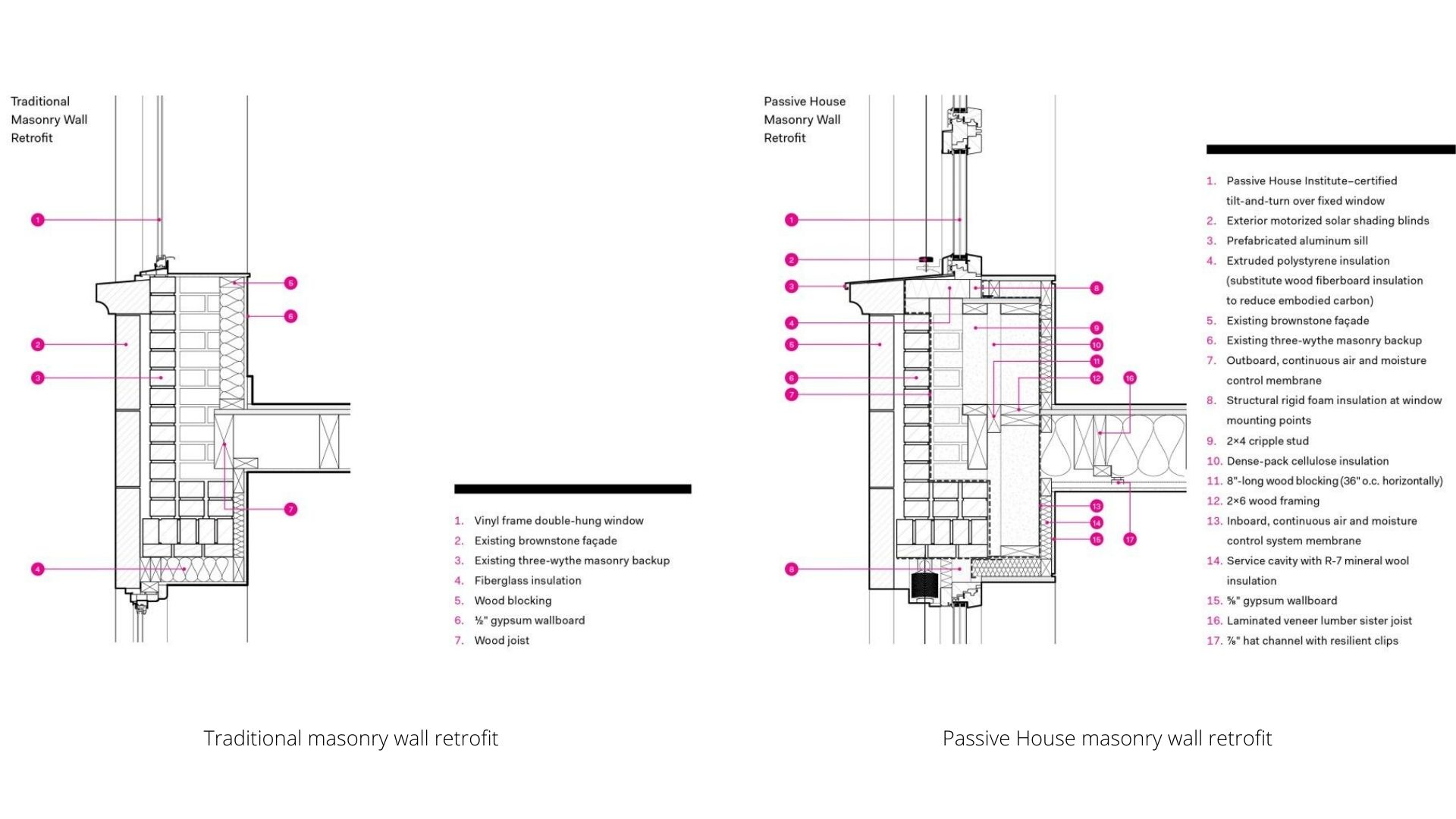

Envelope and insulation

To maximize efficiency, a house needs to perform beyond local building code minimums, so passive houses usually include double to triple the insulation required. To preserve the brownstone’s historic facade, the interior was demolished down to the masonry, and the depth of the front and rear walls was expanded by almost a foot to accommodate no fewer than four types of insulation:

- Mineral wool batts, a type of insulation blanket, has a lower embodied carbon impact than extruded polystyrene (XPS), expanded polystyrene, polyisocyanurate and spray foam at an equivalent R-value.

- Dense-packed cellulose is a frequently used type of insulation made with shredded recycled paper, cardboard boxes and other discarded waste paper products that’s thought to have a negative embodied carbon impact.

- Some XPS was used around the windows, which “essentially sit in a bathtub of insulation,” says Mandl, as well as under the cellar slab.

- Intello, a “smart” air- and moisture-control membrane, wraps the interior of the building, allowing vapor through but not air, “so moisture in the walls can always dry out,” explains Mandl. It’s smart because it’s adaptable: In winter, it slows the rate at which vapor can enter, protecting against condensation. In summer, it’s fully open to vapor to help quickly dry out the interior. “The air tightness is really what gets a passive house that extra level of comfort and operational savings,” notes Mandl.

Windows

Mandl and Johnston replaced their old vinyl-framed, double-hung windows with new ones from Optiwin, which are certified by the Passive House Institute, an independent research institute that promotes passive houses. “When closed,” says Mandl of the wood-framed, triple-paned, triple-gasketed tilt-and-turns, “they’re very tightly sealed.”

To control the amount of solar heat gain the home experiences during New York’s sweltering summers, the architects installed Hella motorized blinds by Peak on the outside of the front south-facing windows. When open, they tuck behind the brownstone, disappearing from view. (They’re also installed on the north-facing facade, where they’re used mostly for privacy.) Unlike curtains, this type of exterior solar shading stops UV rays before they penetrate the window’s glass, which means the building can be kept cool with minimal mechanical intervention.

Ventilation, heating and cooling

An energy-recovery ventilator (ERV) gets fresh, filtered air into the airtight building, and recuperates the heat from used air as it exhausts it out through the kitchen and bathroom. Between the ERV, the exterior solar shading and the super-efficient windows, the couple’s climate control needs can be met with a small electric heat pump they use during the months with more extreme temperatures. “A short blast once a day keeps the house warm or cool,” observes Mandl.

But it’s the heat coming off inhabitants, computers, lighting and activities like showering and cooking that does the lion’s share of warming the house in the winter. “So if you’re cold but don’t want to turn on any active heating,” adds Mandl with a smile, “invite some friends over for dinner.”

Electricity and solar energy

The couple decided to turn to solar to meet their drastically reduced electricity needs, and installed an 18-panel, 5.76 kW photovoltaic system on their roof. The Brooklyn SolarWorks array powers all their appliances—an induction stovetop, a fridge, an oven, a dishwasher and a washing machine—along with the ERV, the heat pump and their electric vehicle. They charge their BMW i3 once a week using a charging station installed in their front yard.

“The building is two-family,” notes Mandl, referring to the garden-level rental unit they renovated to the same standard. “So there’s two of every appliance. Even so—and including charging our car—we produce more electricity than we use on an annual basis.”

Reusing and retrofitting with a purpose

As much as 30 percent of building materials delivered to a construction site end up as waste. Not wanting to contribute to such a dismal statistic (or the nearly 600 million tons of construction-related waste generated in the U.S. in 2018), Mandl and Johnston sought to preserve and reuse whatever they could. They worked with their contractor LB General Contracting to save all the ornate woodwork; most was reused, including all the old doors. “Anything we didn’t use was donated to Big Reuse, a non-profit here in Brooklyn,” explains Mandl. “Hopefully it finds its way into another renovation.”

According to the World Green Building Council, buildings are currently responsible for 39 percent of global energy-related carbon emissions. For Mandl and Johnston, decarbonizing existing building stock is key to a renewable future. “The embodied carbon is too vast,” says Mandl, “and the architectural history too beautiful to leave behind.”